So you’re thinking about breeding goats, but not sure what to do?

Well you’ve come to the right place! This Beginner’s Guide to Goat Breeding should help you understand the process, and what you need (and don’t need) to do.

Who is this Guide For?

I’ve written this guide primarily for new goat owners, or those of you considering getting your first goats. It is based on our experiences here at GottaGoat Farm, and all the research we continuously do about goats. I know it can be difficult weeding through all the information available these days, so my goal is to try and present the “best practices” surrounding goat care for the small farmer, hobby farmer, or goat “enthusiast”.

There is certainly a lot of information on this subject, so I’ve tried to consolidate some of the key areas that you’ll need to take into consideration before choosing to breed goats.

I get a lot of questions about goats, and try to provide the best information possible, while always keeping in mind the health, safety, and well-being of the goats (and other animals). However, please note we are not vets, and any information here should not be used as a substitute for obtaining appropriate vet care for your own animals! Also note, we primarily raise and breed miniature goats here, and although most information is specific to these breeds, much of it is common to all breeds of goats.

Why Would You Breed?

Let’s start out with a simple question: Why would you breed your goats?

- The obvious answer is “to have more goats.” There are many reasons why you might need or want additional goats, whether you’re keeping them for your own herd or selling them, but this is the ultimate result of breeding. Goats can have anywhere from one to six kids at a time (twins or triplets being common with most breeds), so it won’t take long before you have a LOT of goats!

- You are planning to milk your goats. If you have a dairy breed of goat, then in order to produce milk, your goat must be bred and have kids. However, remember the point above – you will now have additional goat kids to care for, so you’ll need to prepare for these kids and have a plan in place on what will happen to them.

What Do You Need?

Another kind of obvious question, but it does raise some additional considerations. You will of course need both a female goat (doe) and male goat (buck). However, not everyone is equipped to house bucks (nor do they necessarily want to keep them) – see the discussion below on keeping bucks – so you may have to plan for how you’ll access a buck for your breeding purposes.

Additionally, you’ll want to consider “who” you are breeding. If you are raising goats for pets, the lineage of the parents might not be of as great importance as their health and behaviour. However, if you are planning on raising milking goats, or showing your goats, the background of the goats that you choose to breed may be of greater significance. You will want to know their lineage, health information, and potentially milk production records.

When Do You Breed?

When it comes to timing your breeding, it’s important to know that many of the larger goat breeds are seasonal, and only breed from late August to January. However, with some breeds (such as Nigerian Dwarf goats), they could be bred at any time of the year. We typically breed our goats in the late fall or early winter, so the kids will be born a little later in the spring. We have very long, cold winters here, and don’t want to risk having new babies until late March at the earliest!

When planning your breeding schedule, keep in mind that the length of their pregnancy ranges from 145 to 152 days (roughly five months). For miniature goats, they tend to be on the earlier side, so be prepared for your doe to start “kidding” as early as 145 days from when she was bred.

About the Does (female goats of breeding age):

A female goat kid (often called a doeling) may reach puberty as early as 3 months. At this time, she may show signs of her first “heat” (estrus), but this doesn’t mean she should be bred at that age. Although there are different views on the matter (often depending on the reason for breeding), it is important to ensure the doe is mature and healthy enough to go through a pregnancy. A good rule of thumb is that your doe should reach 80% of her full-grown weight before you breed her. So, for example, if your doe will be 75 pounds at maturity (typical for a Nigerian Dwarf goat), you could breed her when she weighs approximately 60 pounds (if she is otherwise in good health). Some does grow larger and faster than others, so in terms of age, your doe may be ready to breed when she is a year old, but others might not be ready until they’re a little older.

As your doe is developing, you should start to track her heat cycles, as it is during their heat that you will breed them with the buck. Does typically go into heat every 18-21 days, and it will last from one to three days. However, it is in that first day or so that your doe will be most receptive to the buck, so understanding her heat cycle is very important.

When a doe is in heat you may notice some of the following behaviours:

- VERY loud and excessive bleating (almost all of our does cry/yell very noticeably when they are in heat)

- Tail wagging

- Mounting other does or being mounted by other does

- Mucous discharge and/or swelling of vulva

Some does may exhibit several of these behaviours, but others may show no signs at all (or the signs are hardly noticeable). If you can, try to make note of any of these behaviours (even if they are very subtle), and the dates they occur. This can be especially helpful when you are trying to plan out your breeding dates.

If you still don’t see your doe go into heat, there are some other options to try:

- Try keeping them with a wether (a wether is a “fixed” or castrated male goat). Although some wethers show no interest in the does, we have found that one of our wethers is a great indicator of when a doe is in heat. If he is around the does, he will try to mount them when they’re in heat, and he’ll even exhibit some other “buck” behaviours (see below).

- Use a “buck rag” to help stimulate the doe. This is a rag that is rubbed all over a stinky buck (yuck) and kept in a sealed container to preserve that lovely aroma. When presented to a doe over several days, she should show greater interest in it when she comes into heat. In some cases, it might even help bring about her heat. We haven’t had to use this method here, but the theory sounds pretty reasonable.

Get to know your goats! You will be much better prepared to notice differences from their normal behaviours, which in turn will help you more easily identify when they are in heat.

Track your doe’s heat cycles! We keep ours listed in a spreadsheet, and note whenever they show signs of being in heat. This way we can track how long their heat cycles are, and when their next expected heat would be.

If you are currently milking your doe, you can continue to do so and still breed her. However, it is recommended that you stop milking a couple months before she is due, to let her body prepare for her new kids. Once she has her kids, you can start milking her again, provided she is in good health and still able to provide for the nutritional needs of the kids. Most diary goats are bred each year to continue producing a regular supply of milk.

About the Bucks (male intact goats of breeding age):

Bucks are breeding machines! We have seen our little bucklings trying to mount their sisters when they are only a couple weeks old! Although at this age they are not able to actually breed, it’s amazing to see how natural and instinctive this behaviour is for them. Bucks can potentially breed as young as seven weeks old, so if you have young bucks in with their moms and sisters, they may need to be removed or closely monitored until they are weaned.

As for when you can breed a buck, it is good practice to wait for them to mature a bit. By the time a buck is between six to eight months old, he can usually successfully breed a doe, but some bucks may take a bit longer to reach their sexual maturity. It may also be the case that your doe is not attracted to a younger buck, as they have not yet learned all of the “buck” behaviours that most attract the females. If you have multiple does to breed, it may be necessary to use more than one buck: even though they WANT to breed all the time, they may have a limit as to how many successful breedings they can perform. As well, breeding will take its toll on the buck, so make sure you provide for their extra nutritional needs during this time, and keep them in the best of health!

What is Rut?

Bucks usually go into a hormone-induced state called “rut”. This is typically strongest starting in early fall, and lasts several months. With our Nigerian Dwarf goats, we find they start their rut in late August, and it continues usually until March.

The behaviours that bucks exhibit can be quite comical. They do the following things to attract the does, all in hopes of completing their mission to breed (and note, they do this whether or not a doe is present)!

- Tongue flapping

- Blubbering and yelling (newcomers to our farm often think it’s someone screaming when they hear the bucks doing this)

- Spitting and snorting

- Urinating (I know, this part is kind of gross, but they urinate on themselves, all over the backs of their legs and stomachs, and all over their faces. They even drink their own urine, and can often get “urine scald” from this behaviour. If you get too close, they may even pee on you!)

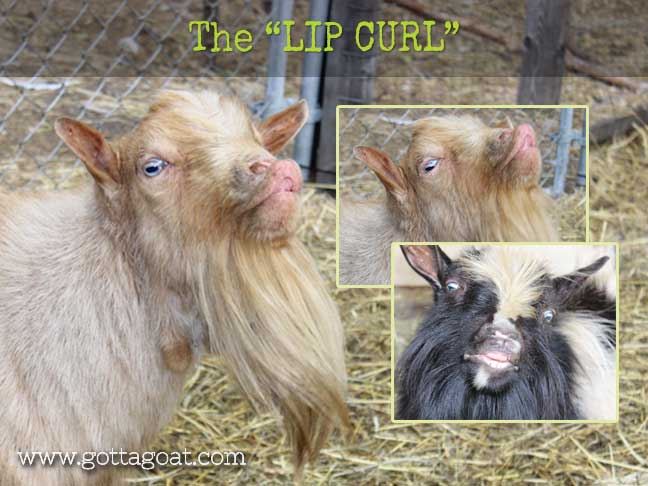

- Lip curling (seen most often when they have just urinated on themselves)

- Mounting each other (and sometimes anything else that gets within reach)

- Become more aggressive (even the sweetest bucks get pretty crazy at this time. Our bucks are mainly more aggressive with each other, and it is not uncommon to find their poor heads quite scratched and bloody from all the extra fighting they do during this time.)

During rut especially, bucks will be STINKY, STICKY and NOISY. If you only have a small number of does to breed, you might consider finding someone who will offer “stud services” rather than purchasing your own buck(s). However, this can present its own challenges, as many farms are practicing stricter biosecurity policies. This means they do not allow other goats to enter their property, nor do they allow their goats to leave their property. Any new goats are only brought onto the farm after a quarantine period to help minimize the risk of diseases being introduced into the rest of the herd. Ultimately, you may end up having to purchase your own bucks, as there may not be any other options available in your area.

I’ve included some videos below of our bucks in rut, just so you can see (and hear) for yourself what they are like. Make sure to turn on the sound!

The boys (bucks) in rut… If anyone hasn't been around male goats when they are in rut, it is quite the experience. Their hormones go crazy, and they are loud, blubbering, sticky and STINKY! And this goes on for months!

Posted by GottaGoat Farm on Monday, January 15, 2018

A little more of the noises that the bucks make when in rut (so make sure to turn on the sound). It really does get loud around here, although I think they tend to put on more of a "show" when we come over to visit with them!

Posted by GottaGoat Farm on Monday, January 15, 2018

A few things to consider about keeping bucks:

- Bucks will need to be kept separate from the does, especially with goats who are able to breed year round. This means providing them with adequate housing, fencing, etc., in a separate area. There are some people who try to keep them with their does all the time, but this can present its own issues:

- It will be difficult to know exactly when the does are bred (so it will be harder to be prepared for when they have their kids)

- Bucks can be dangerous around pregnant does

- Bucks can be dangerous around young goat kids

- It will be difficult to prevent does from getting pregnant again soon after they have kids

- As goats are herd animals, bucks will need a “buddy” to thrive. You will need to keep multiple bucks together, or have a wether with your buck to keep him company.

- You will need secure fencing for your bucks, as they will try very hard to get to any does in heat!

- Bucks and does should not share a fence – bucks will happily breed through a fence!

- As mentioned above, bucks are STINKY and NOISY! This means if you have close neighbours, or your buck pasture is close to your living accommodations, you may need to adjust your plans on where they will be kept.

Now I don’t want to paint a completely negative picture about owning bucks. As you can see, they certainly come with their challenges, but if you are able to keep your own bucks, they are fun to have around and very entertaining. Our bucks can be so sweet too, and really enjoy their scratches and affection from us (although not everyone is willing to cuddle up to a stinky buck!). By the time spring comes around here, they shed a lot of that sticky undercoat, and they are clean and beautiful again (just in time to go back into rut)! It is also very convenient to have your own bucks, as it is so much easier to coordinate their “dates” with the does in heat.

If you decide to get your own buck, it may actually be wise to plan for future breeding and purchase two unrelated bucks. This gives you options when choosing the best buck to breed with your does (or their future kids), and prevents you from having to breed a father to his daughter in the future (the concept of line-breeding vs. in-breeding is a whole other discussion – there is definitely some interesting reading out there about this if you are interested in goat genetics!).

How Do You Breed Them?

The act of breeding your goats is actually the easy part! The goats will know what to do if the conditions are right…

Be prepared! If you know your doe’s heat cycles, you can plan in advance to have an area ready for breeding her with your buck, and you can time it so that the kids are born at the most suitable time of year. However, no matter how well you plan, it will often be the case that your doe goes into heat during the worst storm, or coldest day of the year, and you may just have to wait until her next heat happens!

When it comes to the actual breeding “date”, there are a few different scenarios that may occur:

- You have your own buck.

- If you know your doe is in heat, then that makes this process pretty straight-forward. You will need to move the doe and buck together, and let them “do their thing”! Having a separate area all ready to take them will help a lot. This can be a stall, a small pasture, or really anywhere you can put them together safely without too many distractions. Quite often, once they see each other, it is “love at first sight” and the whole process is over pretty quickly!

- If the doe isn’t standing still, you might have to give them a little more time together (anywhere from a few hours, to a day or two), and monitor during that time to see if he has actually bred her. It may also be possible to help out a little and even hold her for him.

- In any case, you should easily be able to tell if he was successful, as there will be a definite milky discharge from her if she was bred. We have one little buck at our farm who is quite the character during his breeding sessions: once he is done, he literally propels himself backward and falls over. He is very dramatic (but at least we know he completed his job)!

- Some people choose to keep their doe(s) in with their buck for a while so they do not have to monitor their heat cycles as closely. Typically this type of breeding situation requires keeping them together for at least three weeks, to ensure the buck is around at the point when she goes into heat. Breeding your goats in this way may be more convenient in some ways, but can make it a bit more challenging to pinpoint your doe’s exact due date.

- If you know your doe is in heat, then that makes this process pretty straight-forward. You will need to move the doe and buck together, and let them “do their thing”! Having a separate area all ready to take them will help a lot. This can be a stall, a small pasture, or really anywhere you can put them together safely without too many distractions. Quite often, once they see each other, it is “love at first sight” and the whole process is over pretty quickly!

- You are taking your goat to a buck to use their “stud service”.

- If this is the case, everything discussed above applies, however, you will also have to get your doe to the buck’s farm. This usually requires that you’ve got a plan in place so when she goes into heat, you can bring her to the buck. If you’re lucky, it won’t take very long and your doe will be bred!

- Depending on the type of arrangement you have with that farm, you may also leave her there for an extended period of time to ensure she is bred. In that case, you may have to plan on additional charges for having them feed and care for her while she is there.

- You have leased or borrowed a buck.

- This situation is similar to the first scenario above (having your own buck), but the buck needs to come to your farm, so these details would need to be determined in advance with the farm from which you are leasing him. They may require that you sign a contract with them, and you might also want to ensure your insurance would cover any costs in the event the buck gets injured while on your property.

- You can choose to keep the leased buck in with your doe(s) for either just the time he needs to breed her (which may only be a few minutes or hours if he is able to breed her right away), or you might have the buck stay with your does for up to three weeks to cover all of them during the different times they go into heat. In this case, you will also have to ensure you have adequate accommodations for the buck, as well as the proper feed for him during this time.

In all cases where you are bringing your goats to another farm, or having goats from another farm come to your place, there is an increased risk of disease (that goes both ways). Many farms choose to test regularly for common diseases in their herd, however, these farms may not allow you to use their buck unless you have also performed the same testing on your herd. At the very least, you should inspect any farm where you are taking your goat, or from which you are using their buck, to ensure that the animals appear healthy and that you are comfortable with your choice to use their services.

Note the exact date on your calendar (if you know it), or the date range your doe was exposed to the buck, since it will be between 145-152 days from this date that your doe should have kids. If the breeding was not successful, she will exhibit signs of going into heat again in 18-21 days, so you will want to keep an eye on this too. Keeping this information in a spreadsheet will help to easily calculate due dates (using some simple formulas), and gives you a great place to store and look up any information about your goats!

If you are planning on breeding multiple does, you may want to breed at least a couple of the does around the same time, so that their kids can socialize and grow up together. However, having too many does go into labour at the same time might be a handful, so staggering some of their due dates might be beneficial. Planning out your breeding schedule will also depend upon how well equipped you are for their birthing needs (Do you have additional help when they start to give birth? Veterinary services when required? Adequate “kidding or birthing stalls” for each expectant doe? Are you able to provide care and housing for all of the new kids?).

What Happens Next?

Now comes the really fun part – the kids! If all has gone well with your breeding, you will now be caring for your pregnant doe for the next five months, and will soon get to experience the amazing miracle of having goat kids. Just remember your doe’s nutritional needs will be changing as she develops, and you will want to take good care of her to ensure the health of both her and her developing kids.

Hopefully this has helped provide some guidance about how to breed your goats. I am currently working on a new eBook about Goat Kidding, so keep in touch, as I hope to have this available soon.

Good luck and Happy Breeding!

I have two does with the same father but different mothers – half sisters. Can I breed the buck (son) of one mother with the other mother or is the too close of a relationship? We are breeding fainting goats as pets.

Sorry for the late reply 🙂

One of the outcomes of “line breeding” (breeding relatives) is that the “good traits” of the related goat will be concentrated, but so will the “bad traits” (and sometimes recessive characteristics will become more apparent). So when deciding whether or not to breed relatives, you want to be sure that your sire has the genetic traits that you would want to see in the resulting kids. A good rule of thumb is not to breed full brothers and sisters, so in your case, this mating should be ok, as long as the sire has the genetic qualities you would want to see in the kids. There is always the risk that some recessive traits will also show up, and if that is the case, you may not want to use that same sire for future breedings. There are many in-depth articles written on this subject (and the science behind it). Have a look at: http://www2.luresext.edu/goats/training/appendixI.html and https://georgiaorganics.org/for-farmers/line-breeding-for-better-livestock/.